|

Case Report

Hepatic cirrhosis with portal hypertension secondary to alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency and autoimmune hepatitis in pregnancy: A case report

1 Junior House Officer, Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

2 Consultant, General Surgery, Royal Brisbane and Women's Hospital, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

3 Consultant, Obstetric Medicine, Royal Brisbane and Women's Hospital, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

4 Consultant, Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Royal Brisbane and Women's Hospital, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

Address correspondence to:

Stephanie Galibert

1 Butterfield Street, Herston, QLD 4029,

Australia

Message to Corresponding Author

Article ID: 100132Z08SG2022

Access full text article on other devices

Access PDF of article on other devices

How to cite this article

Galibert S, O’Rourke N, Wolski P, Schmidt B. Hepatic cirrhosis with portal hypertension secondary to alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency and autoimmune hepatitis in pregnancy: A case report. J Case Rep Images Obstet Gynecol 2022;8(2):38–44.ABSTRACT

Introduction: Previously, women with cirrhosis rarely became pregnant due to hypothalamic-pituitary dysfunction. However, with advancements in the care of patients with chronic liver disease, pregnancy is becoming more common in this cohort. We will outline the complex, multidisciplinary approach toward managing an obstetrics patient with portal hypertension in the context of previously decompensated liver cirrhosis.

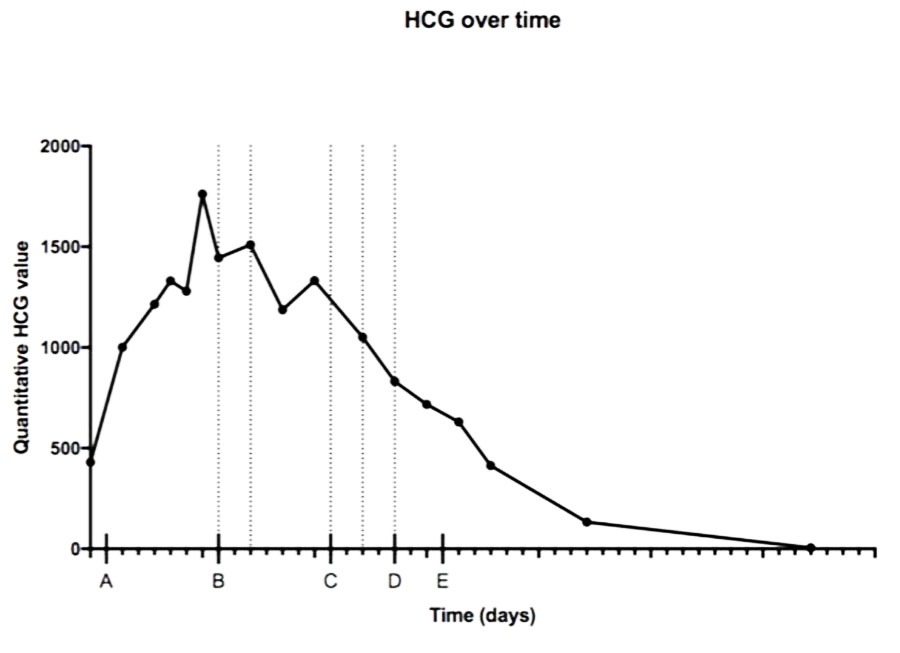

Case Report: A 29-year-old primigravida woman was referred to the Obstetric Medicine Clinic with an unplanned pregnancy at 16 weeks’ gestation. This was on a background of previously decompensated liver cirrhosis and portal hypertension, in the context of alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency and autoimmune hepatitis. The patient had one upper gastrointestinal bleed at 19 weeks’ gestation and underwent three gastroscopies throughout her pregnancy. At 32+6 weeks gestation, she had an elective lower uterine segment Caesarean Section and delivered a healthy liveborn female.

Conclusion: Currently, there are no studies that explore pregnancy outcomes in women with cirrhosis secondary to alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. This case describes the pregnancy of a woman with previously decompensated liver cirrhosis and portal hypertension, in the context of alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency and explores the associated management dilemmas.

Keywords: Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, Cirrhosis, Decompensated liver disease, Portal hypertension, Pregnancy

Introduction

The prevalence of cirrhosis in women of reproductive age is increasing (approximately 45 in 100,000) [1],[2],[3], resulting in a higher incidence of pregnancy in this population. Historically, women with cirrhosis have had reduced fertility due to anovulation, resulting in hypothalamic-pituitary dysfunction [4],[5],[6]. However, pregnancy is becoming more common in this cohort as a result of improved care of patients with chronic liver disease [5],[7].

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a rare chronic liver disease that is characterized by progressive hepatocellular inflammation and necrosis that can result in hepatic cirrhosis [8]. Autoimmune hepatitis is reported to be more common in women, especially during their childbearing years. While most autoimmune disorders are better controlled during pregnancy due to a state of immune tolerance, some women experience severe flares of AIH [8]. Prednisolone and Azathioprine are the treatments of choice during pregnancy to treat and prevent flares [9],[10]. Historically, AIH has been associated with preeclampsia, hepatic decompensation, maternal death, early fetal loss, prematurity, low birth weight, and a high rate of Caesarean sections [10]. Recent studies have demonstrated more favorable outcomes in this cohort, however they remain at increased risk of adverse pregnancy and neonatal complications compared to the general population [9],[10],[11]. As a result, these women require close monitoring during pregnancy by a multidisciplinary team.

The pathophysiology of alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency is poorly understood and is reported to affect approximately three million people globally [12] . There are no studies to date that specifically investigate alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency related cirrhosis in pregnancy.

Pregnancy in the context of cirrhosis is more likely to be complicated in the presence of associated portal hypertension. The increased risks associated with portal hypertension include variceal hemorrhage, hepatic failure, encephalopathy, malnutrition, and splenic artery aneurysm [6],[13]. Maternal mortality in pregnant women with cirrhosis ranges between 0% and 14%; older studies report higher rates, while more recent studies report rates <2% [13]. This is likely to have improved with better management of variceal bleeding and liver failure. Other pregnancy related complications are also more common in women with cirrhosis including gestational hypertension, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, preeclampsia and post-partum hemorrhage [7],[13],[14].

Fetal complications are also more common in the setting of maternal cirrhosis [3],[7],[13]. The majority of studies report an increased risk of prematurity and low birth weight [7],[9],[13],[14],[15]. There is conflicting data on the risk of stillbirth, with a number of studies reporting increased risk [5],[14],[16], while others show no difference compared to the general population [2],[9],[17]. Neonatal deaths are more common (0–8%) and are likely related to prematurity and low birth weight [13].

Case Report

A 29-year-old primigravida, Caucasian, Australian woman with cirrhosis and portal hypertension was referred to the Obstetric Medicine Clinic at the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, with an unplanned pregnancy at 16 weeks’ gestation. She was known to the Hepatology team at the same hospital, however, had been lost to follow up more than two years prior to this presentation and had limited contact with any medical practitioner during that time.

Our patient was known to have cirrhosis secondary to homozygous alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency and associated autoimmune hepatitis. She initially presented with amenorrhoea at the age of 14, at which time no clear cause was found. She then developed fatigue and rectal bleeding, and was referred to a Gastroenterologist who diagnosed autoimmune hepatitis. She trialed many different therapeutic agents including Prednisolone, Azathioprine, Spironolactone, Frusemide, and Propranolol, however all were self-ceased due to side effects. Prior to this pregnancy there had been 4–5 episodes of variceal bleeding. Her most recent presentation with variceal bleeding was one year prior, at which time an endoscopy showed grade 3 varices. Her other past medical history included mild asthma, iron deficiency, medullary sponge kidney and psoriasis.

The patient had a complex social background. She was living alone with no consistent family support and was not employed during the pregnancy. The social work team were heavily involved in this patient’s care and provided invaluable assistance with access to housing, financial advice and postnatal support. She ceased smoking upon confirming that she was pregnant and denied any alcohol intake.

At the first Obstetric Medicine appointment she was normotensive (BP 120/70) and weighed 84.6 kg (BMI 27.8). She had marked peripheral edema and splenomegaly (span ~20 cm). The liver was not palpable, there was no ascites and no spider nevi were present.

The patient’s pathology is outlined in Table 1; these results gave her a model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score of 12. A MELD score of 10 or more is associated with 83% sensitivity and specificity in predicting a serious cirrhosis related complication during pregnancy or postpartum [18] (Table 1).

She was referred to the Obstetric Medicine Clinic by her General Practitioner at 16 weeks’ gestation. Subsequently, her first contact with the Obstetrics team was at 18 weeks when she presented to the Emergency Department with abdominal pain, nausea and hematemesis. During this admission she underwent banding of her eseophageal varices and non-bleeding gastric varices were also identified. At this time, she was prescribed Propranolol, intravenous Pantoprazole and a unit of packed red blood cells as her Hemoglobin was 72 g/L. Following this admission, a multidisciplinary team (MDT) was convened which included Obstetrics, Maternal Fetal Medicine, Obstetric Medicine, Hepatobiliary Surgery, Anesthetics and Gastroenterology. This team discussed her case regularly to formulate the safest plan for the duration of the pregnancy.

Following this admission, she proceeded to have an MRI which showed a markedly cirrhotic liver with evidence of portal hypertension and extensive perigastric and paraesophageal varices extending into the mediastinum. The largest varices measured up to 20mm in depth. There were no varices identified in the anterior abdominal wall. Also of note, she had massive splenomegaly with the spleen spanning at least 250mm in craniocaudal length (Figure 1).

The MDT agreed that a series of elective endoscopies for treatment of varices should be performed leading up to the delivery. She proceeded to have two elective endoscopies at 27 and 30 weeks. On both occasions, non-bleeding esophageal varices were identified and banded. Non-bleeding gastric varices were also noted.

She had monthly Obstetric ultrasounds to monitor fetal growth and wellbeing. At 28+1, estimated fetal weight (EFW) was 1481g (93%), amniotic fluid index (AFI) was normal and Dopplers were normal. Five days prior to delivery at 32+1, EFW was 2386g (94%) and again, AFI and Dopplers were both normal. She received antenatal Betamethasone to assist in fetal lung maturation.

The timing and mode of delivery was discussed extensively amongst the MDT. Given the patient had known gastric and esophageal varices which required three episodes of banding during the pregnancy, she was at risk of bleeding prior to delivery. This was of increasing concern with advancing gestation due to worsening portal hypertension and her progressively hyperemic vasculature. In addition, there was concern about the safety of repeated Valsalva maneuvers during labor, which carries with it the risk of variceal rupture and subsequent haemorrhage. Given these considerations, and also taking into account that her MRI showed no varices in the anterior abdominal wall, a preterm elective Caesarean Section was deemed to be the safest option. In determining the timing of delivery, the main consideration was weighing up fetal maturity compared to the risk of maternal bleeding. The MDT agreed to proceed with delivery at 32+6 weeks.

At the time of delivery, the longstanding thrombocytopenia due to hypersplenism (platelet count of 47 × 109/L) was managed with two bags of pooled platelets prior to the Caesarean. In view of the thrombocytopenia and bleeding risk, General Anesthetic (GA) was recommended by the Anesthetist. She was at increased risk of post-partum hemorrhage due to thrombocytopenia in the setting of hypersplenism with portal hypertension. In addition, as she would be receiving a GA, this also increased bleeding risk due to increased vasodilation. Intra-operatively, there was general ooze from the outset of surgery and many large, dilated blood vessels were visualized. During the procedure, steps were taken as a preventative measure in case of significant post-operative bleeding. The cervix was manually dilated prior to closing the uterus in case a Bakri had to be inserted and a pelvic drain was inserted intra-operatively. She was given Tranexamic acid, Oxytocin, and Misoprostol to minimize bleeding and improve uterine tone. At the completion of the Caesarean, uterine tone was good and she had an estimated blood loss of 1.6 L (Figure 2).

She gave birth to a liveborn female weighing 2269 g (82nd centile) with Apgars of six and eight, at one and five minutes respectively. The baby was transferred to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit for one day, then she spent 28 days in the Special Care Nursery. The main issues which required management included transient tachypnoea of the newborn, jaundice and hypoglycemia. The baby was discharged home after 29 days.

In the post-partum period, the patient was quite fluid overloaded and required diuresis with Frusemide. Hemoglobin was stable post-operatively and her drain had minimal output so was removed day two post procedure. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis required careful consideration given her thrombocytopenia. Once her platelet count was above 50 × 109/L, the decision was made, in conjunction with Obstetric Medicine, to commence subcutaneous Enoxaparin. She was discharged day seven post-delivery.

Since discharge from hospital, she has been well and attending her Obstetric Medicine and Hepatology Outpatient appointments. Two weeks post-partum, her liver function became more deranged and the Hepatologists commenced Prednisone. Unfortunately, the patient felt increasingly unwell after two doses, so was unable to continue this course. Despite this, her liver function tests improved and are continue to be monitored by the Hepatologists. She had a repeat endoscopy six weeks post-partum, which demonstrated non-bleeding grade 2 esophageal varices which were banded and bulging at the gastric fundus on retroflexion which likely represented paragastric varices (awaiting further investigation). Six weeks postpartum, she had an Implanon (subdermal, progestogen implant) inserted for contraception.

Discussion

With improved awareness and management of underlying liver conditions, pregnancy is becoming more common in women with liver cirrhosis and portal hypertension. The incidence has increased from 2.5 per 100,000 (2007) to 6.5 per 100,000 pregnancies (2016) over ten years in the United States and from 2 per 100,000 to 14.9 per 100,000 pregnancies from 2000 in 2016 in Canada [3],[19]. Previously, pregnancy was significantly less common in the context of cirrhosis due to metabolic and hormonal changes that contribute to amenorrhoea and anovulation [5]. As a result, limited data exists regarding the management and outcomes for pregnancy in the context of cirrhosis with portal hypertension.

There are a number of studies that exist advising on the management of pregnancy in women with non-cirrhotic AIH, however few of those comment specifically on those with subsequent cirrhosis. The first systematic review with meta-analysis on AIH in pregnancy was recently published by El Jamaly et al. [20]. This study found that AIH is associated with increased risk of premature birth and low birth weight. Unfortunately, the review does not explore outcomes in cirrhosis.

The most significant complication of cirrhosis and portal hypertension during pregnancy is variceal bleeding, which occurs in up to 30% of women. The risk increases up to 78% in women with pre-existing varices [21],[22],[23]. Maternal mortality rates are as high as 20–50% with each episode of variceal bleeding [21]. The risk of this complication is greatest during second trimester and during the second stage of labor due to increasing portal hypertension caused by increased circulating blood volume and pressure of the gravid uterus on the inferior vena cava. The American College of Gastroenterology recommended screening for esophageal varices in the second trimester, once fetal organogenesis is complete and prior to the greatest risk of bleeding during delivery [21]. Fetal hypoxia is the greatest concern when performing an endoscopy, however, the risk is mitigated by ensuring that women are positioned in the left lateral position to avoid vascular compression and are given adequate intravenous hydration [21],[24]. It is widely accepted that beta-blockers and endoscopic hemostasis are first line management for esophageal varices, however, there are limited data on the outcomes with these interventions during pregnancy. Octreotide appears to be safe in acute variceal bleeding, along with less common interventions such as transjugular intrahepatic systemic shunts and liver transplantation discussed in case reports only.

Pregnancy outcomes differ between cirrhosis with and without portal hypertension, as well as in cases of non-cirrhotic portal hypertension. In cases of compensated cirrhosis with no evidence of portal hypertension, there is a lower risk of complications [3]. Cirrhosis with portal hypertension is associated with additional risks of hepatic decompensation and encephalopathy, ascites, hepatorenal syndrome and bacterial peritonitis [25]. Non-cirrhotic portal hypertension is not associated with reduced fertility, in contrast to cirrhotic portal hypertension [26]. Liver function is mostly preserved in non-cirrhotic portal hypertension, therefore the main risks are variceal hemorrhage and hematological complications in the context of hypersplenism [27],[28].

Given the complexity of cirrhosis and portal hypertension in the context of pregnancy, the establishment of an MDT is essential to optimize maternal and fetal outcomes [21],[28]. If possible, the instigation of the MDT should be prior to conception to allow for pre-pregnancy counseling and prophylactic variceal banding [1].

Literature regarding the safest mode of delivery in patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension is sparse. Studies demonstrate that women with chronic liver disease have higher risk of requiring Caesarean Section; however, there are no studies that compare outcomes between Caesarean and vaginal birth [1],[13],[21],[24],[29]. Given the concern in relation to increased portal pressures caused by repeated Valsalva maneuvers during labor, many experts recommend Caesarean Sections. In the study carried out by Tolunay et al. [14], all women with esophageal varices were delivered by Caesarean. Most studies show a significantly increased risk in requiring a Caesarean Section in women with cirrhosis compared to the control group [2],[4],[14],[30].

There are no studies that specifically comment on the decision-making process guiding timing of delivery. Westbrook et al. [18] studied the utility of using the MELD score to predict outcomes in cirrhotic patients. They found that the median gestational week of delivery was 36 weeks, ranging between 24 and 38 weeks for women with cirrhosis. A higher MELD score was associated with a higher risk for preterm birth.

The majority of studies that comment on fetal outcomes in women with cirrhosis have found that infants are more likely to be born premature and have low birth weight [1],[2],[14],[30]. Another study conducted by Westbrook et al. [10] looked at fetal outcomes in women with AIH associated cirrhosis compared to non-cirrhotic AIH. Live birth rate was significantly lower in women with cirrhosis (58%) versus non-cirrhotic patients (83%) (p value = 0.02). This was consistent with the findings of Huang et al. [19], who reported that in comparison to the general population, there is an increased risk of fetal death among women with cirrhosis (0.7% vs. 2.8% respectively). In contrast, both Stokkeland et al. [9] and Braga et al. [8] found that there was no statistically significant association between AIH and stillbirth or neonatal mortality. However, these studies did not comment on the proportion of cirrhosis in their participants.

Conclusion

In conclusion, given the increasing prevalence of cirrhosis and associated portal hypertension in women of reproductive age, it is pertinent that we study the implications for pregnancy and the associated challenges with delivery. This case emphasizes the role of diligent antenatal care and the essential role of a multidisciplinary approach toward these complex cases to optimize maternal and fetal outcomes.

REFERENCES

1.

Faulkes RE, Chauhan A, Knox E, Johnston T, Thompson F, Ferguson J. Review article: Chronic liver disease and pregnancy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2020;52(3):420–9. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

2.

Hagström H, Höijer J, Marschall HU, et al. Outcomes of pregnancy in mothers with cirrhosis: A national population-based cohort study of 1.3 million pregnancies. Hepatol Commun 2018;2(11):1299–305. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

3.

Flemming JA, Mullin M, Lu J, et al. Outcomes of pregnant women with cirrhosis and their infants in a population-based study. Gastroenterol 2020;159(5):1752–62.e10. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

4.

Shaheen AAM, Myers RP. The outcomes of pregnancy in patients with cirrhosis: A population-based study. Liver Int 2010;30(2):275–83. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

5.

Tan J, Surti B, Saab S. Pregnancy and cirrhosis. Liver Transpl 2008;14(8):1081–91. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

6.

Lee NM, Brady CW. Liver disease in pregnancy. World J Gastroenterol 2009;15(8):897–906. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

7.

Gao X, Zhu Y, Liu H, Yu H, Wang M. Maternal and fetal outcomes of patients with liver cirrhosis: A case-control study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021;21(1):280. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

8.

Braga A, Vasconcelos C, Braga J. Autoimmune hepatitis and pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2020;68:23–31. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

9.

Stokkeland K, Ludvigsson JF, Hultcrantz R, et al. Increased risk of preterm birth in women with autoimmune hepatitis – A nationwide cohort study. Liver Int 2016;36(1):76–83. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

10.

Expert Panel on Neurologic Imaging, Kirsch CFE, Bykowski J, et al. ACR appropriateness Criteria® Sinonasal disease. J Am Coll Radiol 2017;14(11S):S550–9. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

11.

Schramm C, Herkel J, Beuers U, Kanzler S, Galle PR, Lohse AW. Pregnancy in autoimmune hepatitis: Outcome and risk factors. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101(3):556–60. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

12.

Townsend S, Newsome P, Turner AM. Presentation and prognosis of liver disease in alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;12(8):745–7. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

13.

Rahim MN, Pirani T, Williamson C, Heneghan MA. Management of pregnancy in women with cirrhosis. United European Gastroenterol J 2021;9(1):110–9. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

14.

Tolunay HE, Aydin M, Cim N, Boza B, Dulger AC, Yıldızhan R. Maternal and fetal outcomes of pregnant women with hepatic cirrhosis. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2020;2020:5819819. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

15.

Ajne G. Chronic cholestatic liver disease and pregnancy – Not to be confused with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. BJOG 2020;127(7):885. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

16.

Palatnik A, Rinella ME. Medical and obstetric complications among pregnant women with liver cirrhosis. Obstet Gynecol 2017;129(6):1118–23. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

17.

Grønbaek L, Vilstrup H, Jepsen P. Pregnancy and birth outcomes in a Danish nationwide cohort of women with autoimmune hepatitis and matched population controls. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018;48(6):655–63. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

18.

Westbrook RH, Yeoman AD, O’Grady JG, Harrison PM, Devlin J, Heneghan MA. Model for end-stage liver disease score predicts outcome in cirrhotic patients during pregnancy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;9(8):694–9. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

19.

Huang AC, Grab J, Flemming JA, Dodge JL, Irani RA, Sarkar M. Pregnancies with cirrhosis are rising and associated with adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes. Am J Gastroenterol 2022;117(3):445–52. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

20.

El Jamaly H, Eslick GD, Weltman M. Systematic review with meta-analysis: Autoimmune hepatitis in pregnancy. Scand J Gastroenterol 2021;56(10):1194–204. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

21.

Tran TT, Ahn J, Reau NS. ACG clinical guideline: liver disease and pregnancy. Am J Gastroenterol 2016;111(2):176–94. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

22.

Peitsidou A, Peitsidis P, Michopoulos S, Matsouka C, Kioses E. Exacerbation of liver cirrhosis in pregnancy: A complex emerging clinical situation. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2009;279(6):911–3. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

23.

Chaudhuri K, Tan EK, Biswas A. Successful pregnancy in a woman with liver cirrhosis complicated by recurrent variceal bleeding. J Obstet Gynaecol 2012;32(5):490–1. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

24.

Stelmach A, SŁowik ł, Cicho? B, et al. Esophageal varices during pregnancy in the course of cirrhosis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2020;24(18):9615–7. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

25.

Morton A, Laurie J, Hill J. Portal hypertension in pregnancy – Concealed perils. Obstet Med 2020;13(3):142–4. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

26.

Sumana G, Dadhwal V, Deka D, Mittal S. Non-cirrhotic portal hypertension and pregnancy outcome. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2008;34(5):801–4. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

27.

Keepanasseril A, Gupta A, Ramesh D, Kothandaraman K, Jeganathan YS, Maurya DK. Maternal-fetal outcome in pregnancies complicated with non-cirrhotic portal hypertension: Experience from a Tertiary Centre in South India. Hepatol Int 2020;14(5):842–9. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

28.

Aggarwal N, Negi N, Aggarwal A, Bodh V, Dhiman RK. Pregnancy with portal hypertension. J Clin Exp Hepatol 2014;4(2):163–71. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

29.

Ma K, Berger D, Reau N. Liver diseases during pregnancy. Clin Liver Dis 2019;23(2):345–61. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

30.

Puljic A, Salati J, Doss A, Caughey AB. Outcomes of pregnancies complicated by liver cirrhosis, portal hypertension, or esophageal varices. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2016;29(3):506–9. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Author Contributions

Stephanie Galibert - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Nicholas O'Rourke - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Penny Wolski - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Bart Schmidt - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Guaranter of SubmissionThe corresponding author is the guarantor of submission.

Source of SupportNone

Consent StatementWritten informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this article.

Data AvailabilityAll relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Conflict of InterestAuthors declare no conflict of interest.

Copyright© 2022 Stephanie Galibert et al. This article is distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium provided the original author(s) and original publisher are properly credited. Please see the copyright policy on the journal website for more information.