|

Case Series

Two cases of isolated tubal torsion: Presentation, evaluation, and management

1 Resident Physician, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States

2 Attending Physician, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States

Address correspondence to:

Jordann-Mishael Duncan

MD, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Pennsylvania Hospital, 800 Spruce Street, Philadelphia, PA,

United States

Message to Corresponding Author

Article ID: 100096Z08JD2021

Access full text article on other devices

Access PDF of article on other devices

How to cite this article

Duncan JM, Banks E. Two cases of isolated tubal torsion: Presentation, evaluation, and management. J Case Rep Images Obstet Gynecol 2021;7:100096Z08JD2021.ABSTRACT

Introduction: Isolated tubal torsion is a rare event with an incidence of 1 in 1.5 million women. Predisposing factors of isolated tubal torsion include intrinsic causes such as hydrosalpinx, tubal adhesions, and tubal ligation; extrinsic causes include ovarian masses, pelvic adhesions, and pregnancy. The gold standard for diagnosis and treatment is laparoscopy.

Case Report: The first clinical case is 33-year-old nulliparous female with a history of hydrosalpinx who presented to the emergency department with left lower quadrant pain accompanied by nausea and emesis. Pelvic ultrasound showed a left hydrosalpinx with normal Doppler venous flow to the left ovary. On physical exam, she had severe abdominal tenderness, but no guarding or rebound. She underwent a diagnostic laparoscopy secondary to concern for isolated tubal torsion. On diagnostic laparoscopy a necrotic, torsed left fallopian tube was visualized and left salpingectomy was performed. The second clinical case is a 25-year-old nulliparous female with a past surgical history of a right salpingo-oophorectomy who presented to the emergency department with left lower quadrant pain and nausea. Pelvic ultrasound showed a complex left adnexal mass. After 24 hours of observation, the patient underwent a diagnostic laparoscopy for persistent pain which revealed left isolated tubal torsion for which a left salpingectomy was performed.

Conclusion: Isolated tubal torsion is a rare occurrence but should be included in the differential for a woman presenting with acute abdominal pain, without evidence of ovarian torsion especially if a tubal mass is present on imaging.

Keywords: Acute abdominal pain, Adnexal masses, Hematosalpinx, Hydrosalpinx, Laparoscopy, Pelvic adhesions, Torsion

Introduction

Ovarian torsion is a fairly common cause of acute abdominal pain in women. The incidence in all women in a 1 year period is about 5.9 per 100,000 [1]. Isolated tubal torsion is a rare event with an incidence of 1 in 1.5 million women [2]. Cases of tubal torsion have been documented throughout all stages of a woman’s reproductive life. Predisposing factors of isolated tubal torsion include intrinsic causes such as hydrosalpinx, tubal adhesions, and tubal ligation; and extrinsic causes include ovarian masses, pelvic adhesions, and pregnancy [3]. Diagnosis can be delayed due to the rarity of this condition and nonspecific symptoms on presentation [4]. Laparoscopy is the gold standard for diagnosis and treatment [4]. This report presents two cases of isolated tubal torsion and their diagnosis using imaging and diagnostic laparoscopy at a large academic health center.

Case Series

Case 1

A 33-year-old nulliparous female presented to emergency department with one day of left lower quadrant abdominal pain not alleviated by oral or intravenous analgesics. The patient reported nausea and emesis. She denied fever and chills. Her past medical history included a history of ovarian cyst rupture at 14 years old, and an incidentally noted hydrosalpinx that had been present for six months at the time of her presentation. On presentation, the patient’s vitals were within normal limits and her abdominal exam was significant for severe tenderness infraumbilically and in left lower quadrant without rebound or guarding. Labs showed a negative quantitative serum beta human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG), hemoglobin of 13.4 g/dL, platelets of 213 THO/uL and no evidence of leukocytosis (white blood cell count 9.8 THO/uL).

Pelvic ultrasound showed normal appearing ovaries without sonographic evidence of ovarian torsion. Color flow and spectral Doppler demonstrated normal arterial and venous blood flow and waveforms in the bilateral ovaries. Medial and adjacent to the left ovary was an elongated anechoic cystic structure measuring 4.85 × 5.45 × 3.58 cm (Figure 1). Further imaging was performed to rule out other causes of acute abdomen. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis showed no acute abdominal or pelvic process, small volume pelvic ascites and redemonstrated the small to moderate sized left hydrosalpinx. The gynecology service was then consulted for further evaluation and recommendations for management.

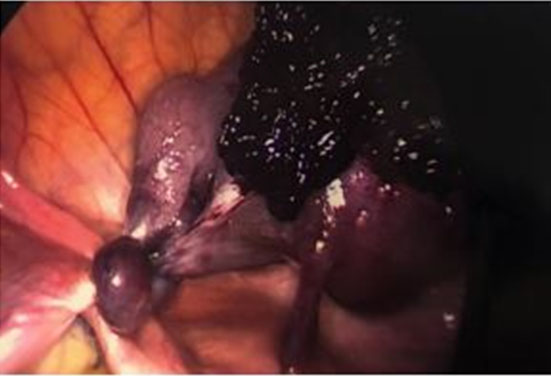

Based on the abdominal exam findings and hydrosalpinx noted on imaging, the decision was made to proceed with diagnostic laparoscopy. On laparoscopic survey, the bilateral ovaries and the right fallopian tube appeared normal. The left fallopian tube was found to be torsed three times, dusky in appearance, enlarged, and distended with old blood (Figure 2). After detorsion of the tube, there was no improvement in its appearance, and the decision was made to proceed with left salpingectomy. The procedure was uncomplicated with an estimated blood loss of less than 10 mL. The patient did well postoperatively and was discharged on postoperative day 0. The left fallopian tube was sent to pathology and the final pathology diagnosis confirmed hematosalpinx with torsion.

Case 2

A 25-year-old nulliparous female presented to the emergency department with two days of severe left lower quadrant abdominal pain unrelieved by oral analgesics and moderately improved with intravenous analgesics. She reported nausea, but denied emesis, fever, and chills. This patient’s history was significant for bilateral ovarian cysts for which she had a laparoscopic right salpingo-oophorectomy and left ovarian cyst aspiration ten years prior for ovarian torsion with pathology significant for a sclerosing stromal tumor of the right ovary, a rare but benign ovarian tumor. On presentation, her vitals were within normal limits. Her physical exam was significant for moderate tenderness to palpation in the left lower quadrant, but no signs of an acute abdomen. Laboratory results showed a negative quantitative serum beta HCG, normal hemoglobin of 13.8 g/dL and mild leukocytosis of 13.1 THO/uL. In light of patient’s history of a sclerosing stromal tumor, tumor markers were sent; HCG, alpha fetoprotein, lactate dehydrogenase, carcinoembryonic antigen, cancer antigen 19-9, and cancer antigen 125, all returned within normal limits.

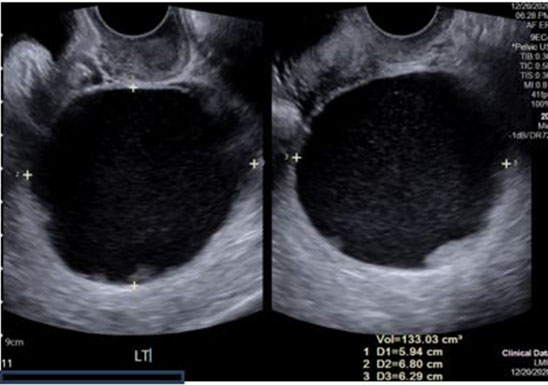

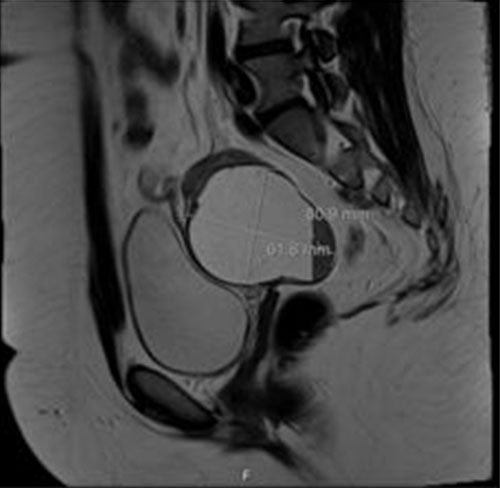

A pelvic ultrasound demonstrated normal arterial and venous flow and waveform to the left ovary. Right ovary was surgically absent. As shown in Figure 3, a complex 5.9 × 6.8 × 6.29 cm left adnexal/pelvic cul-de-sac cyst was seen which demonstrated mobile low-level echoes and an echogenic, avascular solid component peripherally. Further imaging was obtained. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen and pelvis showed an 8 cm left adnexal cystic mass favored to represent large hematosalpinx (Figure 4), with slight thickening of the right uterosacral ligament which may be related to endometriosis.

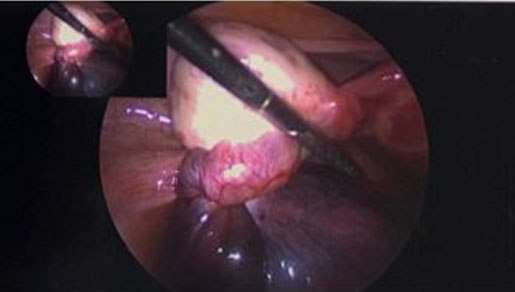

The gynecology service was consulted and the patient was admitted for observation given her continued abdominal pain. Her pain did not improve, and she thus underwent diagnostic laparoscopy on hospital day two. On laparoscopic survey there was no evidence of adhesions or endometriosis. The left ovary was normal in appearance. The left fallopian tube, however, was noted to be enlarged to approximately 10 cm, dark purple in appearance and torsed three times as shown in Figure 5. The decision was made to perform a left salpingectomy due to tubal torsion. There were no complications with the procedure, estimated blood loss was less that 10 mL and the patient was discharged on postoperative day 0. The final pathology revealed tubal hemorrhage and necrosis consistent with tubal torsion.

Discussion

Isolated tubal torsion is a rare cause of acute abdominal pain. The exact cause of isolated tubal torsion is unknown, however, several risk factors have been identified. Risk factors for isolated tubal torsion include intrinsic pathology such as Morgagni hydatids, tubal ligation, hydrosalpinx, pyosalpinx, adhesions, endometriosis, abnormal peristalsis, long fallopian tube or mesosalpinx and spiral course of the fallopian tube [2],[3],[5]. It also includes extrinsic risk factors such as ovarian cysts, tumors, previous pelvic surgery, hyperstimulated ovaries, pregnancy (normal or ectopic), venous congestion and trauma [2],[3],[5]. Both patients had risk factors for tubal torsion including hematosalpinx, history of ovarian cysts, previous pelvic surgery and possible endometriosis.

High clinical suspicion is needed for the appropriate diagnosis and treatment. Laparoscopy remains the gold standard for both diagnosis and treatment [4]. In patients who desire to preserve fertility, laparoscopic detorsion of the fallopian tube should be performed to attempt to restore vascular blood supply and preserve tubal integrity and function [6],[7]. There have been several proposed methods for stabilizing the ovary in adnexal torsion such as oophoropexy, however, this has not been shown to prevent recurrence [7]. If the fallopian tube is noted to be necrotic even after detorsion or the patient does not desire future fertility, salpingectomy may be performed [6]. Prompt diagnosis with laparoscopy is key given the risk of necrosis of the fallopian tube and impact on fertility.

In a retrospective study in 2020 by Balasubramaniam et al., 17 patients had laparoscopically confirmed isolated tubal torsion, 88% presented with lower abdominal pain as a predominant symptom, 47% of patients reported nausea and vomiting, 17.6% reported dysuria, and 11.7% reported diarrhea [4]. The classic finding in tubal torsion is sudden onset sharp severe abdominal pain radiating to the flank, which was seen in this study in 52.9% of patients [4]. In this study, 82.3% of patients had abdominal tenderness on exam and 29.4% had a palpable mass on exam [4]. Neither of our patients presented with classic tubal torsion abdominal pain radiating to the flank, however, both presented with acute onset abdominal pain with nausea and vomiting and typical exam findings of abdominal tenderness. In this same study, 41% of patients presented with leukocytosis and on ultrasound hydrosalpinx was seen in 70.5% of patients [4]. Consistent with what was reported in the Balasubramaniam et al.’s study, one of our patients presented with leukocytosis, while the other had a normal white blood cell count. Similarly, both of our patients had abnormal tubal findings on ultrasound, with one patient presenting with a hydrosalpinx and the other presenting with hematosalpinx. In the Balasubramaniam et al. study, 7 patients underwent additional imaging such as CT scan. In all 7 cases the CT did not confirm the diagnosis. Both of our patients had further imaging with CT and MRI which did not confirm the diagnosis. This shows that although further imaging should be obtained to rule out other causes of abdominal pain, clinical suspicion for isolated tubal torsion has to be present and laparoscopy is definitive management and diagnosis.

Conclusion

Although tubal torsion is not a common etiology of acute abdominal pain in a reproductive age woman, it is important to keep this on the differential diagnosis to allow for prompt diagnosis and treatment with laparoscopy. As ovarian torsion is a much more common occurrence, tubal torsion is often excluded from the differential for acute abdominal pain when imaging findings show no ovarian pathology and demonstrates normal blood flow to the ovaries. High clinical suspicion for tubal torsion should be maintained in a woman presenting with acute abdominal pain and evidence of tubal pathology on imaging.

REFERENCES

1.

Robertson JJ, Long B, Koyfman A. Myths in the evaluation and management of ovarian torsion. J Emerg Med 2017;52(4):449–56. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

2.

Canda MT, Erkan MM, Demir N, Camli D. Acute isolated tubal torsion with hematosalpinx in a premenopausal woman: The importance of the whirlpool sign. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2020;27(3):570–2. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

3.

Krissi H, Shalev J, Bar-Hava I, Langer R, Herman A, Kaplan B. Fallopian tube torsion: Laparoscopic evaluation and treatment of a rare gynecological entity. J Am Board Fam Pract 2001;14(4):274–7.

[Pubmed]

4.

Balasubramaniam D, Duraisamy KY, Ezhilmani M, Ravi S. Isolated fallopian tube torsion: A rare twist with a diagnostic challenge that may compromise fertility. J Hum Reprod Sci 2020;13(2):162–7. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

5.

Phillips K, Fino ME, Kump L, Berkeley A. Chronic isolated fallopian tube torsion. Fertil Steril 2009;92(1):394.e1–3. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

6.

Fadıloğlu E, Dur R, Demirdağ E, et al. Isolated tubal torsion: Successful preoperative diagnosis of five cases using ultrasound and management with laparoscopy. Turk J Obstet Gynecol 2017;14(3):187–90. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

7.

Blitz MJ, Appelbaum H. Management of isolated tubal torsion in a premenarchal adolescent female with prior oophoropexy: A case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2013;26(4):e95–7. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Dr. Banks as well as the Pennsylvania Hospital residency program for taking excellent care of these patients

Author ContributionsJordann-Mishael Duncan - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Elizabeth Banks - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Guaranter of SubmissionThe corresponding author is the guarantor of submission.

Source of SupportNone

Consent StatementWritten informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this article.

Data AvailabilityAll relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Conflict of InterestAuthors declare no conflict of interest.

Copyright© 2021 Jordann-Mishael Duncan et al. This article is distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium provided the original author(s) and original publisher are properly credited. Please see the copyright policy on the journal website for more information.