|

Case Report

Complete molar pregnancy: A case report

1 Resident Physician, Obstetrics and Gynecology, SUNY Downstate Health Sciences University, Brooklyn, NY, United States of America

2 Urogynecology fellow, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO, United States of America

3 Attending physician, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Kings County Health and Hospital Center, Brooklyn, NY, United States of America

Address correspondence to:

Ranjitha Vasa

450 Clarkson Avenue, Brooklyn, NY 11203,

United States of America

Message to Corresponding Author

Article ID: 100201Z08RV2025

Access full text article on other devices

Access PDF of article on other devices

How to cite this article

Vasa R, Thompson M, Soyemi SA, Gosine V. Complete molar pregnancy: A case report. J Case Rep Images Obstet Gynecol 2025;11(1):64–68.ABSTRACT

Introduction: Complete hydatidiform mole, a form of gestational trophoblastic disease, occurs when one sperm fertilizes an empty ovum. Complete trophoblastic proliferation is associated with elevated serum beta human chorionic gonadotropin levels and absence of a fetus. Classic clinical features include abnormal vaginal bleeding, hyperemesis, and enlarged uterus for gestational age. Less common features include hyperthyroidism, early onset pre-eclampsia, and bilateral ovarian thecalutein cysts.

Case Report: We present a case of a complete molar pregnancy of a woman who presented to the emergency department at 18 and 4/7 weeks with complaints of irregular vaginal spotting. Serum beta human chorionic gonadotropin level was noted to be 59,401. Transvaginal ultrasound notable for absence of intrauterine gestation with complex heterogeneous material within the uterus. The patient underwent suction dilatation and curettage. Histological examination of curettings confirmed a complete hydatidiform mole. The patient with persistently elevated blood pressures post-operatively necessitated workup for pre-eclampsia, which was negative. Given elevated blood pressures, the patient was started on Labetalol 200 mg twice daily with improvement one month post-procedure. Today, she no longer requires anti-hypertensive medication and beta human chorionic gonadotropin level has appropriately down trended.

Conclusion: Our case highlights the need for early imaging to detect abnormalities like hydatidiform moles, which pose significant risks. Early detection improves patient outcomes and ensures proper post-operative care.

Keywords: Case report, Hydatidiform mole, Molar pregnancy, Obstetrics, Pregnancy

Introduction

Gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD) is a group of trophoblastic tumors originating from the placenta with the potential to become invasive. It is composed of the following: hydatidiform mole (complete or partial), invasive mole, placental site trophoblastic tumor, and choriocarcinoma. The most common form of GTD is the hydatidiform mole, also known as molar pregnancy [1].

The frequency of hydatidiform mole in North America has been noted to occur in 1:500–1:2000 pregnancies. The risk for developing complete molar pregnancy is about 1.9 times higher in women younger than 21 years of age and older 35 years of age, and about 7.5 times higher in women older 40 years of age [2].

The complete hydatidiform mole is most commonly diploid and occurs when one sperm fertilizes an empty ovum with the 46, XX karyotype. Less common, di-spermic fertilization (when two sperm fertilize one ovum) results in the 46, XY karyotype. Both are abnormal fertilizations and result in the genetic content being purely paternal in composition [3],[4]. The aberrant proliferation of both cytotrophoblasts and syncytiotrophoblasts with diffuse hydropic villi characterize this form of pregnancy. Often, these patients present with higher-than-expected serum beta human chorionic gonadotropin levels (bHCG), which can exceed 100,000 IU/L. With the diagnosis of a complete hydatidiform mole, there is an increased risk of persistent trophoblastic disease or malignant complications compared to a diagnosis of an incomplete molar pregnancy [1],[5].

A partial hydatidiform molar pregnancy is characterized by karyotype and occurs when two sperm fertilize a normal ovum with the 69, XXY, or 69, XYY and less likely 69, XXX karyotype. The hydropic villi tend to be less proliferative and are interspersed within normal chorionic villi. Serum bHCG for partial molar pregnancies is often consistent with normal ranges of pregnancy [1],[5].

A molar pregnancy is usually suspected based on the following clinical features: abnormal vaginal bleeding in early pregnancy, uterus large for gestational age, vaginal passage of grape-like vesicles, pain from benign ovarian theca-lutein cysts, exaggerated pregnancy symptoms including hyperemesis, hyperthyroidism, and early onset pre-eclampsia [6].

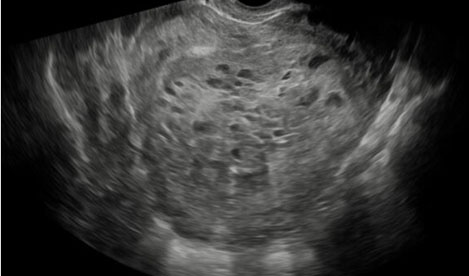

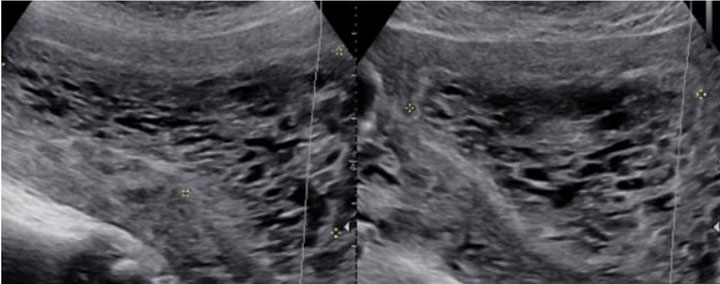

Imaging through transvaginal ultrasound often can diagnose molar pregnancy before 12 weeks. Ultrasound can show either a honeycomb or a fine vascular appearance [7]. Ultrasound confirmation of a complete molar pregnancy after 12 weeks of gestation is characterized by a lack of fetal parts and scant embryonal development with a classic “snowstorm-like” appearance within the uterus. Specifically, the “snowstorm-like” appearance is indicative of hydropic villi and intrauterine hemorrhage. The ovaries can often contain multiple large theca-lutein cysts secondary to ovarian hyperstimulation from elevated bHCG levels [8]. Meanwhile, ultrasound confirmation of a partial mole can be slightly more difficult as there is usually the presence of a fetus and/or a large placenta [8].

Suction curettage is the standard method for management, regardless of uterine size with the use of oxytocin and prostaglandin analogs post-procedure in the event of significant uterine hemorrhage [9]. Total abdominal hysterectomy can be a reasonable option for patients who do not wish to preserve their fertility and are greater than 40 years old [9].

Of note, chest radiography or computed tomography should be considered pre-operatively if a patient presents with pulmonary symptoms and there is concern for pulmonary metastases. If a patient is rhesus negative, Rhogam should be administered to prevent alloimmunization. Patients must be readily available for weekly bHCG until values are undetectable [9],[10].

As stated previously, molar pregnancies are typically identified earlier in pregnancy; however, here we report a complete molar pregnancy identified in the second trimester at 18 weeks of gestation. Therefore, this case not only demonstrates physical findings unique to a complete molar pregnancy, but also reinforces need for swift intervention once identified.

Case Report

A 35-year-old Caribbean Black woman G5P2022 whose first day of her last menstrual period was 11/29/23 at 18 and 4/7 weeks gestation presented to one of the primary county hospitals, located in Central Brooklyn, for an evaluation of intermittent episodes of vaginal spotting in the setting of known pregnancy. At the time of gynecologic assessment, the patient denied abdominal pain or heavy vaginal bleeding. The patient otherwise denied any other complaints such as abnormal discharge, itching, fever/chills, nausea/vomiting, headache, changes in vision, chest pain, shortness of breath, or calf pain. The patient had immigrated from Trinidad to Brooklyn, New York. She had started prenatal care in her home country but had not undergone any imaging studies to confirm pregnancy. The patient’s obstetrical history was notable for two previous spontaneous miscarriages, one elective medication termination of pregnancy, and two previous normal spontaneous vaginal deliveries. Otherwise, the patient’s medical history and physical examination were unremarkable. Vital signs were notable for blood pressures in the hypertensive range 143–170/82–96. Per patient, she denies prior history of hypertension. The patient declined any signs or symptoms of pre-eclampsia. Speculum examination revealed normal vaginal mucosa with no blood in the vaginal vault with bimanual examination revealing an enlarged anteverted uterus measuring about 20 weeks in gestation with no adnexal masses palpated.

The patient’s serum quantitative bHCG is 59,401 with blood type O+. The remaining laboratory studies were unremarkable. Transvaginal ultrasound showed no evidence of intrauterine gestation with complex heterogenous material within the uterus measuring 8.8×4.9×6.8 cm (Figure 1 and Figure 2). The patient was counseled appropriately about suction dilatation and curettage in the context of suspected complete molar pregnancy, given the absence of a fetus on transvaginal sonogram, elevated serum bHCG level, vaginal spotting, and new onset hypertension. The patient underwent an uncomplicated suction dilatation and curettage. Intra-operatively, tan-colored grape-like vesicles measuring between 1 and 2 cm were noted in the suction tubing (Figure 3). Post-procedure bedside sonogram was performed and revealed a thin endometrial stripe. The patient tolerated the surgery well and was discharged in good health after appropriate clearance from postoperative anesthesia care unit. Post-operatively, appropriate pre-eclampsia laboratory tests were conducted due to the patient’s elevated blood pressure, revealing a urine protein-creatinine ratio of 0.245 and normal serum laboratory results. Given persistently elevated blood pressures post-procedure, the patient was started on Labetalol 200 mg twice daily upon discharge. Pathology assessment of the resected surgical specimen confirmed complete molar pregnancy. The patient’s blood pressures normalized one-month post-procedure and she is no longer taking the prescribed anti-hypertensive. Her post-operative bHCG was closely followed weekly over the course of eight weeks until the value was less than 1.0.

Discussion

Though complete molar pregnancy is rare, the patient in this case report does have several risk factors such as her age, race, and history of two spontaneous miscarriages. While the patient presented here possesses several risk factors for GTD, this case is unique due to the late gestational age at presentation. Albeit, despite earlier detection, the risk of development of post-molar GTN has not been affected [11].

As stated previously, a molar pregnancy is diagnosed using both clinical and ultrasonographic features. Detection of a complete molar pregnancy is made obvious through the recommended imaging in the first trimester of pregnancy; however, the patient in our case did not have any routine imaging confirming pregnancy location or dating [11],[12].

In our patient, the diagnosis of molar pregnancy was made at our facility through ultrasound and confirmed through examination of post-operative pathology well within the second trimester. This case report is unique in that it details a singleton pregnancy well into in the second trimester with a complete molar pregnancy.

It is important to note that patients with complete molar pregnancy may concurrently present with symptoms consistent with hyperthyroidism and preeclampsia [9],[13]. Though quite rare, with prompt surgical management of the molar pregnancy, the signs/symptoms of the conditions should dissipate. There was concern in our patient for possible pre-eclampsia given blood pressure elevation pre- and intra-operatively; however, the patient’s serum laboratory studies were not reflective of this condition. Likely given more time, she may have progressed to develop complications, as she had new onset hypertension associated with the pregnancy.

The decision was made not to administer prophylactic chemotherapy to the patient because, although she was managed with suction dilatation and curettage, the patient did not present with any high-risk features of gestational trophoblastic neoplasm such as serum bHCG greater than 100,000, ovarian theca lutein cysts greater than 6 cm, age greater than 40 years old, and uterine size greater than gestational age.

Conclusion

Standard obstetrical care in industrialized nations worldwide emphasizes early sonographic visualization of intrauterine pregnancy; however, our case emphasizes the importance of visualizing a suspected pregnancy as early as possible to detect the presence of abnormal pregnancies such as the hydatidiform mole. As stated previously, particularly with hydatidiform molar pregnancies, there are adverse patient risks. Early detection of these abnormal pregnancies can enhance positive patient outcomes in addition to appropriate post-operative follow-up. In our case, our patient required immediate post-operative blood pressure control with improvement one month later. In addition, her bHCG levels appropriately declined with close weekly follow-up over an eight-week period.

REFERENCES

1.

De Franciscis P, Schiattarella A, Labriola D, et al. A partial molar pregnancy associated with a fetus with intrauterine growth restriction delivered at 31 weeks: A case report. J Med Case Rep 2019;13(1):204. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

2.

Irani RA, Holliman K, Debbink M, et al. Complete molar pregnancies with a coexisting fetus: Pregnancy outcomes and review of literature. AJP Rep 2021;12(1):e96–107. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

3.

Lawler SD, Fisher RA, Dent J. A prospective genetic study of complete and partial hydatidiform moles. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1991;164(5 Pt 1):1270–7. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

4.

Ohama K, Kajii T, Okamoto E, et al. Dispermic origin of XY hydatidiform moles. Nature 1981;292(5823):551–2. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

5.

Bousfiha N, Erarhay S, Louba A, et al. Ectopic molar pregnancy: A case report. Pan Afr Med J 2012;11:63.

[Pubmed]

6.

Cue L, Farci F, Ghassemzadeh S, Kang M. Hydatidiform Mole. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025.

[Pubmed]

7.

Lima LLA, Parente RC, Maestá I, et al. Clinical and radiological correlations in patients with gestational trophoblastic disease. Radiol Bras 2016;49(4):241–50.

[Pubmed]

8.

Cavaliere A, Ermito S, Dinatale A, Pedata R. Management of molar pregnancy. J Prenat Med 2009;3(1):15–7.

[Pubmed]

9.

Wang Q, Fu J, Hu L, et al. Prophylactic chemotherapy for hydatidiform mole to prevent gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;9(9):CD007289. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

10.

Eagan D, Jeter N. Complete molar pregnancy with transformation to choriocarcinoma of the liver: A case report. Case Rep Womens Health 2016;12:11–4. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

11.

Sun SY, Melamed A, Goldstein DP, et al. Changing presentation of complete hydatidiform mole at the New England Trophoblastic Disease Center over the past three decades: Does early diagnosis alter risk for gestational trophoblastic neoplasia? Gynecol Oncol 2015;138(1):46–9. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

12.

Ottanelli S, Simeone S, Serena C, et al. PP120. Hydatidiform mole as a cause of eclampsia in the first trimester: A case report. Pregnancy Hypertens 2012;2(3):304. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

13.

Pereira JVB, Lim T. Hyperthyroidism in gestational trophoblastic disease – A literature review. Thyroid Res 2021;14(1):1. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Author Contributions

Ranjitha Vasa - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Marae Thompson - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Sarin Abiola Soyemi - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Valini Gosine - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Guaranter of SubmissionThe corresponding author is the guarantor of submission.

Source of SupportNone

Consent StatementWritten informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this article.

Data AvailabilityAll relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Conflict of InterestAuthors declare no conflict of interest.

Copyright© 2025 Ranjitha Vasa et al. This article is distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium provided the original author(s) and original publisher are properly credited. Please see the copyright policy on the journal website for more information.